WHO

The silent killer: why chronic respiratory disease deserves global attention

Multisectoral Action

25 Nov 2024

Humanitarian Studies | 15 Feb 2024

Even before COVID-19 turned the world upside down, it was predicted that 168 million people worldwide would need humanitarian assistance and protection. That represents about one person in 45 globally.

We know that the combination of COVID-19, chronic diseases and poverty present a global health emergency: a ‘perfect storm’. But what does this mean in places with even greater fragility, conflict and uncertainty, especially now that funding for the humanitarian sector is at risk. And especially as, despite promising efforts and important deliberations this year at WHA74, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) usually remain a blind spot in emergency preparedness and response.

The approaches used to prevent, identify and manage COVID-19 will not be feasible in most humanitarian settings. Public health preventive measures such as physical distancing are extremely difficult to implement. Access to testing in humanitarian settings, if available at all, is usually limited to symptomatic testing of those most unwell (though exceptions do occur).

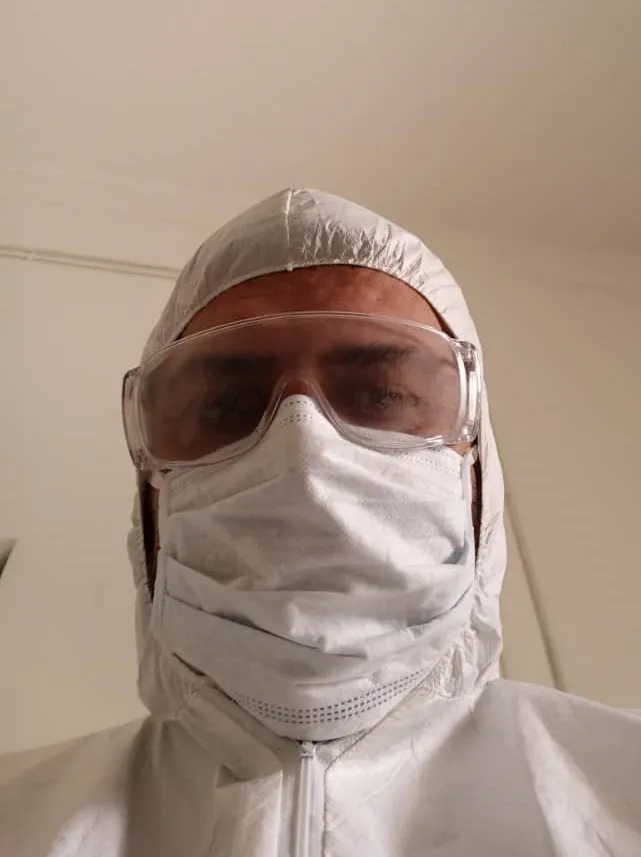

Acute care for those with serious COVID-19 disease is hampered by lack of space, staff PPE and essential equipment, e.g. oxygen and steroids, and the ability to provide end of life care is also lacking. All this has greater impact on people living with underlying chronic conditions (NCDs have themselves been described as another ‘pandemic’).

Despite these challenges, it is possible for health workers in humanitarian settings to manage COVID-19. Primary Care International (PCI), a social enterprise working to strengthen the primary care workforce and systems in a variety of settings globally, recently partnered with WHO to equip clinicians in NW Syria with the knowledge and skills on the management of COVID-19 in already fragile contexts.

Prior to COVID-19 – and despite the overall lack of attention to NCDs in emergencies – some organisations had started to make the steps to integrate management of chronic diseases into humanitarian healthcare systems. This means providing consistent long-term care for transient populations, ensuring continuous access to medication for NCDs and strengthening overall primary healthcare capacity to deliver services within the community.

However, COVID-19 risks reversing the steps made in this area. A WHO survey showed that 69% of countries reported disruption in NCD diagnosis and treatment since the onset of COVID-19. A second round of this survey, just published, shows some improvements but highlights how care for chronic conditions is still badly disrupted.

As we move forward, there are some potential opportunities to seize.

The PCI and WHO partnership in NW Syria continued this year by supporting healthcare workers to manage NCDs in humanitarian settings already impacted by COVID-19. “I see 70-80 patients a day: most of them are Internally Displaced People. Most of the concerns are around chronic diseases, especially Type 2 diabetes and hypertension. COVID-19 has been very challenging.” Downloadable case-based e-learning was developed, supplemented by live workshops, focusing on problem-solving in primary care, clinical skills and patients with multimorbidity.

Looking globally, COVID-19 has revealed the vast number of people living with chronic disease who are unaware of their diagnosis. Integrated screening approaches that incorporate COVID-19, TB, HIV, diabetes and hypertension are being proposed and may help to address this but only if serious attention is paid to weaving vertical programmes into strong primary care systems capable of managing all long-term conditions including NCDs holistically. Now, while we are still dealing with and learning from COVID-19 is the time to get serious about integrated health care.

We have also seen rapid and often innovative adaptations to service delivery for essential medicines that reduce the frequency of interactions with the health facility in humanitarian and resource-poor settings. These range from telemedicine, messaging apps and peer support networks, providing longer medication refills, and different means to deliver medicines, such as ‘patient champions’, younger relatives or motorbike taxis. Instead of policies, guidelines and clinical habits that previously made patients with even well-controlled disease attend clinics monthly, adaptions such as these could now be expanded to provide more convenient, person-centred services.

We need to learn from such opportunities, and share innovations with wider audiences globally – for example via the COVID-19 humanitarian platform – an initiative developed to inform humanitarian professionals on possible adaptations during COVID-19.

We must also push governments and those working in humanitarian settings to ensure that they prioritise a set of essential services, according to their country context, that should be maintained during emergencies. Health sector reforms and expansion of benefit packages like the recent Integrated Package of Essential Health Services in Afghanistan (integrating basic management of diabetes and hypertension) offer an opportunity to include services that were not yet prioritised. The WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Compendium and the Disease Control Priorities interventions have facilitated this process of prioritisation. Various other models can be used in support, such as this adapted list of essential non-COVID-19 health interventions.

COVID-19 is likely to persist in humanitarian settings. We need to look long-term, to strengthen primary care systems to better manage NCD care AND future pandemics. To better include those millions of people in need of humanitarian assistance and protection.

This blog is part of Primary Care Perspectives: an Op-Ed series exploring resilient systems and healthy populations in the context of Covid-19 and beyond.